Saturday, May 31, 2003

Exporting Higher Education: So What Exactly is Transnational Ed?

Together, GATS modes 1 and 3 comprise an alternative to Consumption Abroad now known as Transnational Education. This growing phenomenon is defined by UNESCO-CEPES as: All types of higher education study programmes or sets of courses of study, or educational services (including those of distance education) in which the learners are located in a country different from the one where the awarding institution is based. Such programmes may belong to the education system of a State different from the State in which it operates, or may operate independently of any national education system.Characterized in this way, Transnational Education challenges the supremecy of the campus. It suggests that there can be viable non-campus service delivery models. While Americans tend to have a hard time imagining a real degree program without any on-campus attendance, the concept is not at all difficult for the rest of the world. In most countries, particularly Asian countries, the supply of public higher education has not been able to keep up with the demand during the recent decades of high economic growth. South-East Asian countries have invested in their own tertiary education infrastructure, but they have also been forced to rely on foreign providers. From the Asian perspective, Consumption Abroad as an import is both costly and risky. Currency and students leave the country, and sometimes neither comes back. Technical and managerial skills acquired through advanced training are essential for participation in the high tech/high return global economy. But the "brain drain" as well as the sheer expense of travel and tuition is a high price to pay. Transnational Education is timely, for Asia. Just when economies are cooling off and travel is becoming more restrictive, there may be another option for post-secondary education with a foreign flavor.

posted by Tom at 10:01 AM | Link |

. . .

Friday, May 30, 2003

Exporting Higher Education: The Modes of the GATS

If American colleges and universities want to maintain their favorable balance of international payments, they will have to venture into new territory. All signs indicate that Consumption Abroad is on a downward spiral for some amount of time. In GATS terms, this category is referred to as "Mode 2." "Mode 1" is Cross Border Supply, which is generally understood as traditional, independent-study-style Distance Education. Services are delivered through postal correspondance, radio or television, or the Internet, and are thought of as primarily asynchronous, with no real-time interaction between instructor and student. With the increasing capabilities of videoconferencing and virtual classroom systems, however, the very nature of Cross Border Supply may be changing. Commercial Presence, or "Mode 3," is a more recent approach to the internationalization of higher education, involving the establishment of branches or subsidiaries, which may depend on local partners. There are several variations on this theme, which has been encouraged by a number of South-East Asian countries as a way to meet a burgeoning demand for advanced training and education, while keeping students in their homeland. The forms Commercial Presence has taken have been identified (Nokkalla, dos Santos, Kaufmann, Phillips & Stahl) as: 1) Branch Campus, in which a higher education institution establishes and operates a facility for delivery of services in a country other than the one in which it is based. 2) Twinning, in which institutions of higher education in different countries adopt each other's course design and content -- the European Credit Transfer System is a high-level Twinning mechanism. 3) Franchising, in which an organization in one country delivers all or part of the courses and overall program specified by an institution of higher education located in another country. . . . . . . . . Overall, Commercial Presence suggests a more substantial involvement than Cross-Border Supply. Whether it is done through its own faculty and staff or through intermediaries, the purpose of a Commercial Presence is to provide a brick & mortar location with flesh & blood instructional support.

posted by Tom at 9:00 AM | Link |

. . .

Thursday, May 29, 2003

Exporting Higher Education: Moving Off-Campus?

With rare exceptions, American Universities have never been organized to deliver services off-campus. Some universities, particularly land grants, operate huge outreach programs within their home state. But structurally, university extension divisions tend to be appendages, attached to the main academic body, rather than an inherent part of it. This relationship reflects a deep misgiving about any form of accredited higher education which does not involve non-mediated contact between a credentialed and qualified instructor and the students. Homage is paid to the need reach out and serve more people, even though the prevailing belief is that non-classroom instruction must be second rate. While this view may be widely shared among American educators, practices are quite different outside the US, where educational opportunity is not sustained for so many years at such a high level. Of necessity, other nations have developed different models of higher education, in which non-residential, non-campus formats are more than a mere appendage. The Open University movement in general and the British Open University (BOU) in particular feature a wide range of instructional techniques developed specifically for off-campus delivery. In the case of the BOU, these techniques are used domestically – and also to deliver services internationally; that is, to export higher education services through methods other than Consumption Abroad. Many Australian institutions of Higher Education have also focused on other export categories. While Consumption Abroad of higher education represents 12% of Australia's service exports, the highest in the world, universities there are actively engaged in service delivery to Asia. In one of the few studies ever conducted on Cross Border Supply of Higher Education services, the Australian Vice-Chancellor's Committee found almost 32,000 Australian University students in off-shore programs in 1999, approximately one-third of the total foreign students studying in Australia. Off-shore programs often involve commercial arrangements with foreign organizations and are considered a third mode of service delivery – Commercial Presence. Both the Cross-Border Supply and Commercial Presence modes are fertile areas for growth – and thus, for instructional technology. American universities might need to look beyond Consumption Abroad and consider these other approaches for several reasons: (1) Although Consumption Abroad as a US educational export category grew rapidly in the 1980s and early 1990s, since the mid-1990s, the growth rate has slowed down significantly, (BP p5). The majority of the earlier growth came from Asia, paralleling the growth of many Asian economies during that period. The forces that propelled the growth can no longer be counted on to support thousands of young Indians, Chinese, Japanese, Singaporeans, Malaysians, Indonesians, Thais, and Koreans on US campuses. (2) Major barriers have emerged in the US to the entry of foreign students. As a part of the American response to the events of September 11, 2001, student visa delays and denials have increased dramatically. In addition, the SEVIS tracking system, to be implemented by September, 2003, puts a major burden on international students and US colleges and universities. Administrative obstacles and reporting requirements may make the US a less attractive destination than it it has been for the past several decades. (3) Universities within the European Union (EU) are organizing themselves to attract international students to the campuses of EU member nations. Known as the Bologna Process, after the Bologna Declaration of 1999, Ministries of Education throughout Europe are creating a European Higher Education Zone, featuring a European Credit Transfer System (ECTS). The ECTS will be a powerful recruitment mechanism and an excellent example of market-focused educational policymaking.

posted by Tom at 9:00 AM | Link |

. . .

Wednesday, May 28, 2003

Exporting Higher Education: Introduction

"It would probably surprise most college admissions officials to learn that when accepting a foreign student for study in the U.S., she or he is committing an export,"

Robert Vastine, president of the

U.S. Coalition of Service Industries,

OECD/US Forum on Trade in Educational Services. It is somewhat counterintuitive to think of the economic impact of foreign nationals studying in the US as a US export. It is a service delivered domestically, but it creates an in-flow of funds from abroad. Most exports are delivered to the purchaser. In the case of Higher Education, the purchasers tend to come and pick it up, which can take years. This dynamic puts US colleges and universities in an enviable position. There are very few products or services for which consumers will leave their country of origin in order to pay premium rates and do hard work over a long period of time. Since the late 1990s, about 1.5 million students have made this choice every year, with approximately one-third them opting for American campuses, the most popular destination in the world higher education market. As a result, Higher Education is the fifth largest service sector export in the American economy, with a $76B international surplus as recently as 2000. In fact, almost all information on the internationalization of higher education is derived from this slightly strange and limited view of exported services – studying in a foreign country. Referred to as "Consumption Abroad" in the basic GATS taxonomy of services, it represents just one of the four major categories. However, it has the advantage of good data, collected by UNESCO and many national organizations. Activities such as the "Cross Border Supply" of higher educational services are difficult to track and international data is almost nonexistent, particularly for the US. Researchers such as Larsen (2002) have concluded that "it is sometimes impossible to identify trade in educational services using standard statistics on services trade." Thus, economic estimates of US higher education's international position almost never include any of the different formats through which distance education services are delivered. One might think that universities would want to address this data deficiency and perhaps give themselves even more stature as a service exporter, but there is no interest in doing so. Higher Education in the US continues to be preoccupied with campus-based services. The absolute focus on bringing overseas students to America as the export strategy reflects this narrow view of internationalization.

posted by Tom at 7:00 AM | Link |

. . .

Monday, May 26, 2003

Waiting for the Keanu Reeves of E-Learning?

OK, I just saw 'The Matrix Reloaded' and I really want to do a Transnational Ed post with a bigtime pop cultural jumping off point. No matter how much of a stretch it is. So here goes: The premise of The Matrix is as old as Gnosticism, which appears to be pre-Christian. The cinematic visualization of the race of humans all tucked into their pods was shown in the first of the three flicks -- and it was powerful. It sure got seared into my brain. But the idea of people being largely unaware of how things really are and buying into an imposed, constructed version of reality permeates the history of religion and philosophy. Lack of originality is precisely why the story is so engaging. It draws on the whole tradition of secret knowledge and The One, and stimulates all the feelings we have about that way of looking at the world. Remember, there are two parts to the claim: 1) The world that most people live in is a pretend world 2) Secret knowledge is required, and usually only one special spiritually developed individual can provide it, to free humanity and enable people to experience the real world The Pretend World thought-form works at many levels. Social cohesion seems to require pretense. It reminds me of the way Russians described their work life in the years of disarray following the end of State Communism: The workers pretend to work and the bosses pretend to pay them.There is so much pretending going on everywhere -- which is where I jump over to Transnational Ed. Historically, the obvious dreamworld that participants bought into was the idea that 'Twinning' and 'Franchising' arrangements produce equivalent educational experiences to what degree granting institutions provide at home. Courses are not just about the content they cover -- they are about the way the faculty at a given institution helps students get engaged with the content so that they can learn about it. People who work in Transnational Ed must be plugged into the Matrix when they act as if the Mode 3 ( Commercial Presence) style of service export resembles the way degree granting institutions normally provide their services. And it gets worse. The major private providers in the key Asian markets have all developed proprietary e-learning systems. Informatics, the leading private provider in terms of volume and outreach, has its PurpleTrain. The Hartford Group, subject of yesterday's post, has its My ELearningPortal. If you believe that the e-learning experience derived from riding the PurpleTrain is remotely equivalent to a typical university course, you are definitely plugged way into the Matrix. And yet, there I was buying into the pretense along with everyone else at the Big Education Expo in Singapore back in March -- working my station in the TMC booth, right across from Informatics and their PurpleTrain

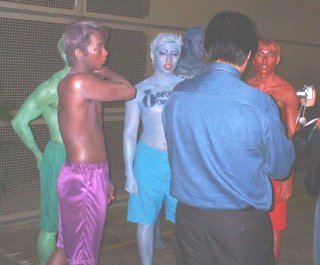

PurpleTrain and other serious educational services were promoted by having half naked male models parade around painted in some strong color, including purple.

I'm not making this up.

. . . . . . . .

How about the second part of the Gnostic claim -- the esoteric part about The One? Here is where the metaphor becomes dangerous. The Russian workers who knew they were pretending kept on doing it anyway. Why? Because even though they knew it was absurd, they could construct no other plausible scenario on their own. They were, in effect, waiting for The One, or at least Some One, to come along and change things. Frankly, I'm not so sure there is a The One, in Transnational Ed or anything else. Or if there is, I'm not so sure that he, she, or it wouldn't want us wake up on our own and start taking serious responsibility for our own education, among other things. Whatever it is we think we need a leader for, we are diminishing in ourselves in that way. E-Learning in general, and Transnational Ed as one arena in which e-learning will be used, will improve when we unplug ourselves from the Matrix, acknowledge the shortcomings, and start creating new and better teaching models. Lots of people need to do this. The peer-to-peer networks emerging, through blogs among other things, are part of what will allow this to happen. I hope.

posted by Tom at 1:31 AM | Link |

. . .

Sunday, May 25, 2003

International Distance Ed: The Investment Front

It caught my attention last week when The Hartford Group, a private distance education company based in Singapore, Hong Kong and Malaysia, launched its IPO. It took some confidence on the part of Chairman K. M. Wong to go forward at this time, no matter how far back it had been planned. Singapore had not yet been declared SARS-free, the economy was tanking in many important sectors -- and Hartford decided to ask for money, at about 20 cents per share. Wong got that much and more: Hartford Holdings made a strong debut, jumping to 34 Singapore cents against its initial public offer price of 20 cents a share. The distance education and e-learning provider was the top traded stock, clocking volume of 25 million shares.Economic Times, May 16, 2003They asked for $1.2M and cashed in with about $2M. That's not a big deal and this isn't a big story. In money terms, it's a small story. But it may be one of those indicators that major shifts are underway. Hartford refers to itself as a "distance education and on-line learning provider." They indicate three delivery modes which they offer: 1) 100% Online mode: Pure e-learning, what they mean above by "on-line learning provider" 2) Hybrid mode : "Some online and some taught mode" 3) 100% Face-to-Face taught mode : In this mode, Hartford provides local faculty to conduct traditional classroom experiences, using syllabi, readings and instructional materials provided by one of Hartford's University Partners. That is, Hartford itself is not an accredited institution. It provides essential services to accredited colleges and universities offering degree programs internationally. Hartford and companies like it are working in the trenches of transnational education. They do the marketing, registration and advising. They provide the facilities. Hartford has Learning Resource Centers (LRCs) in Singapore, Hong Kong, Malaysia, and mainland China. Half the money Hartford raised is for establishing additional LRCs in existing markets and expansion into new markets. This is the basic Transnational Ed equation: A local company like Hartford does the heavy lifting, and an accredited degree granting institution in Australia, the UK or a few other western countries provides content and assessment services. Investors like this model. They bid up the IPO considerably during tough times. I like this model. The Transnational Ed program which I direct works exactly as I described it above. My university works with a different provider -- TMC. This is a competitive marketplace. Auston International Group put out its IPO back in April, but it didn't do as well as Hartford's. TMC, Hartford, and Auston are vying for second place in the regional market for private education services. The leading player by far is Informatics. Hartford showed a profit of $1.6M in FY2002. During that same period, Informatics showed a profit of $21.5M. Wong Tai, Chairman of Informatics, is the brother of Hartford Chairman K. M. Wong, (or, Wong Kock Meng). Yes, there is a sibling rivalry being played out on a world stage. They worked together at Informatics from 1993-199, at which point irreconcilable differences drove them apart. K. M. Wong immediately started The Hartford Group, and there you have it. K. M. did pretty well on his IPO. We'll see how he does on his P&L. Transnational Ed is a lucrative business, but private companies like Hartford sometimes have to spend serious money recruiting students. Nevertheless, investors like the idea.

posted by Tom at 2:27 AM | Link |

. . .

|